The RunGnosis Speculator, Vol II

In this issue you'll learn:

- Why treadmills suck!

- How a Texas Longhorn walk-on became a NCAA Champion.

- How to train our perception of time, which is altered in flow states.

- How those evening drinks impact your recovery & performance.

- A systematic series of Grab Bag fartlek sessions.

Treadmills Suck!

In my nearly 50 years of running, I have not run more than 10 miles total on a treadmill. They nauseate me. I find them to be unbearable torture devices designed to steal every last ounce of pleasure out of any experience of freedom, flow & fun that my running provides.

I know there are many people for whom the treadmill is a necessary evil. I sympathize, but I do not understand. Maybe I don’t care enough for the exercise aspect of running to endure that monotony or the sense of being a caged animal. My distaste sent me on a little research project to explore the wild world of the dreadmill.

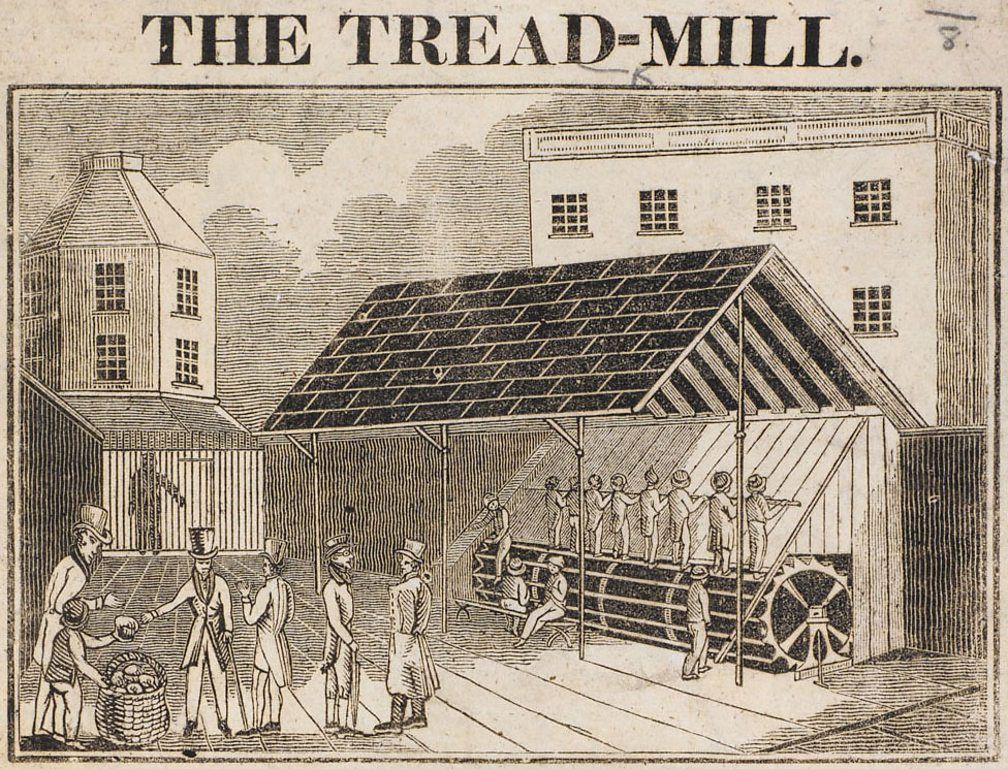

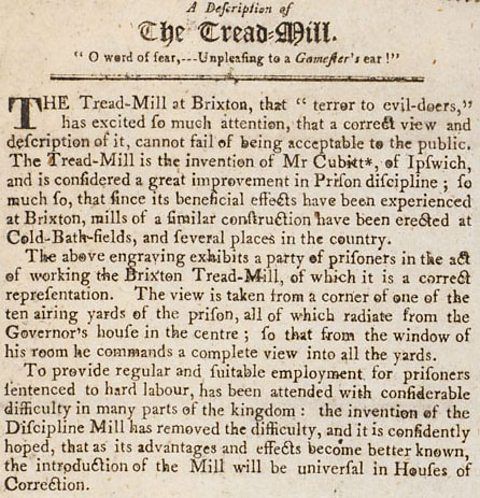

Did you know the treadmill was originally devised as a method of extracting labor from prisoners? In 1817, an English engineer & inventor named William Cubitt noticed local prisoners were slacking off. So he designed a prototype that allowed up to a dozen inmates to climb steps on a moving wheel that could crush grain, pump water or simply "grind air." Through this type of labor, 19th-century prisons enforced a culture of reform & hoped to instill habits of industry. These treadmills would run 8-12 hours a day—8-12 hours of convicts endlessly repeating cycles of hard labor.

If you are interested in more on the history of the treadmill, check out Dan Koeppel's 2019 article in the New York Times. He covers some pretty grim experiences, for example:

This was considered to be more humane, at least compared with earlier methods of punishment, which centered on hanging or exile to British colonies. Hard labor on a treadmill for a fixed term, the theory went, could rehabilitate an offender, who could then return to society and family. Never mind that the prisoner was often left shattered by the experience. Oscar Wilde spent two years on the treadmill as punishment for “gross indecency with certain male persons.” In a poem about his incarceration, he wrote: “We banged the tins, and bawled the hymns, /And sweated on the mill: /But in the heart of every man /Terror was lying still.” Wilde never recovered from the brutal treatment, and he died three years after his release, at age 46.

From Walk-On to NCAA Champion

In a more positive—but fucking crazy—take on treadmill running, Coach Pete Watson revealed his NCAA Championship Distance Medley Relay (DMR) anchor leg, Yaseen Abdalla, upped his weekly training volume nearly 100% over the summer, from 60 miles per week to between 110-120 miles per week. Incredibly, Abdalla apparently does nearly 100 miles a week on the treadmill. Listen below:

Coach Watson reveals Yaseen Abdalla runs nearly 100 miles per week on the treadmill

"He loves the treadmill...he's one of those guys who likes to control everything."

OK, then. Maybe I need to revise my opinion on the treadmill...nah, I don't think so!

But seriously, as a coach, I am always saying that my athletes can be as good as they want to be. Listening to Pete gush about his team & seeing the level of improvement in his athletes only reinforces this point: Once an individual or group commits to becoming excellent & follows through with concrete changes in habits, mindset, & environment, amazing results are possible.

For more on Yaseen’s incredible improvement, check out this excellent article by a former athlete of mine, Taylor Dutch, who ran at Cal Berkeley.

I competed for the Texas Longhorns in the late ’80s/early ’90s & was very proud the men’s team won their first NCAA Championship.

Just in case you'd like to see the DMR win for Texas:

Neurology of Flow States

One of the key aspects of the elusive "zone" or flow state is that our perception of time has a tendency to be altered in ways we deeply appreciate, especially as runners. We tend to be obsessed with time & how we feel as we experience its passing: we track our pace on each rep or each mile, trying to get faster or squeeze more distance out of its duration. We crave the moments where we are completely immersed and absorbed in running & experience an altered sense of time, place, and self.

If you find yourself chasing this particular dragon, this 2018 article in the excellent online journal Nautilus should be of great interest to you.

Some takeaways:

- While there is not a lot of new info on the practical aspects of activating flow, this does help the layperson get an idea of what is happening neurologically. It can be very useful to read this at least once so you have a general idea of what the hell is going on in that three pounds of gray matter.

- From the article:

“A great example of flow state is found in many improvised art forms, from music to acting to comedy to poetry, also known as “spontaneous creativity.” Improvisation is a highly complex form of creative behavior that justly inspires our awe and admiration. The ability to improvise requires cognitive flexibility, divergent thinking and discipline-specific skills, and it improves with training.”

- Running a beautiful race, carving a line on an epic trail run, floating through the final two miles of a sustained long run—these are all examples I’ve experienced of the "spontaneous creative" in running. We can get better & better at this improvisation through developing the skills described above. This should be an active part of our overall approach to training.

- A few potential examples:

Cognitive flexibility means being able to wrap your brain around challenging & novel circumstances that appear in training. This should include cultivating experiences of equanimity, which limit negative emotions, feelings, & feedback loops.

Divergent thinking means coming up with in-the-moment solutions in a free-flowing, nonlinear way. This can occur only if you are open to perceiving problems as they arise. Mindset plays a huge role in this. I highly recommend the work of Carol Dweck where she illustrates challenges & problems as opportunities to learn & grow. She calls it the "growth mindset." It is absolutely crucial to divergent thinking to already be in a growth mindset. Once you’ve developed this growth mindset & overcome problems—see the old Running Rogue podcast (Episode 20 - Overcoming Limits) on becoming a problem-solving motherfucker—you will be open to this unique, free-flowing, nonlinear approach to problem solving. We have to set the foundation, then be able to process conventional problem solving before we can be fluid & flexible enough to access divergent thinking.

Discipline Skills include a wide array of learned, repeated effective thoughts & actions that can be deployed in the moment. These include but are not limited to mantras, songs, cues, gates, quotes, etc. This needs to be developed individually as it must be authentic to be effective. If you import a skill that doesn't work for you, it's a waste of time—or worse: Once a skill doesn't work, we tend to go into a downward spiral that can develop into a negative feedback loop.

Regardless, this is a really valuable topic to work on during a base phase, since you won't have a command performance staring you in the face. Play with these concepts & see what works for you temperamentally & what is effective. - Also from the article:

“Improvising performers are not oblivious; momentary ‘check-ins’ to see how your performance is going can provide necessary environmental (or audience) feedback, helping to revise your approach and optimize performance in real-time.”

These "check-ins" must be practiced in training to hone an automatic process that doesn't require your active engagement. You should be in a position where they are on auto-pilot.

Alcohol, Sleep & Performance

I know some athletes like to have a few drinks in the evening. I frequently get asked what kind of effect alcohol consumption has on performances. This 2020 sleep study provides some concrete results.

My takeaways:

- This study conclusively finds that your sleeping cardiovascular (CV) heart rate function is highly impacted by evening alcohol consumption. This means your body has a harder time recovering when you've had two or more drinks in an evening.

- Sleep is critical for recovery in athletes who are training at high levels. The body does most of its critical recovery as you sleep at night. If your heart rate is increased because you had a few, then you are not going to recover effectively.

- For more on sleep listen to the Huberman Lab podcast episode 2. It's a fantastic overview of sleep from one of the world sleep experts.

- Low-level (1 standard drink for women and 2 drinks for men) drinking has a much less deleterious effect, nearly equal to placebo (no alcohol). High-level drinking (3 standard drinks for women and 4 drinks for men) significantly impacts autonomic & CV heart rates.

- Main takeaway: a little nip ain't gonna hurt you; too much & most of your hard training gains can be nullified simply by your decision to drink.

A Series of Systematic Grab Bag Fartleks

A few years ago I did a podcast episode on Grab Bag Sessions, where I provide a few specific workouts you can rotate on a whim & be sure you get a quality physiological & psychological response from it. The various sessions complement each other very well in combination & can be the basis for a very simple, minimally periodized schedule. It's a pretty good concept & can teach those who are self-coached how to consider the ways these various sessions develop their fitness.

The other day one of my Telos Running athletes needed some alternative sessions as she enters the clinical phase of her medical school education. She's in surgery right now & the hours are crazy & unpredictable. I created a systematic series of fartlek sessions that she can select based on the variety of scenarios she finds herself in. There are two basic phases of this work:

- Phase One - The focus is on getting accustomed to determining the efforts indicated (Steady, Hard, & Fast), while providing a little ladder to go through to be sure there is some progression to the work.

- Phase Two - A significant increase in variability & optionality, where the sessions are still systematically presented, but she is free to select without needing to follow any specific progression. There is an additional element of a float added to the rest for additional difficulty.

It was fun to create this for her so I thought I would add the sessions here for those who might be self-coached & are looking for some spice to add to their training cycle. If you have additional questions about this, just send me an email at sisson (at) rungnosis (dot) com.

Phase One

- 4 min Steady/1 min easy or float

- 3 min Hard/2 min easy or float

- 2 min Hard/3 min easy or float

- 1 min FAST/4 min easy or float

Phase Two

- 9 min Steady/1 min easy or float

- 8 min Steady/2 min easy or float

- 7 min Steady/3 min easy or float

- 6 min Hard/4 min easy or float

- 5 min Hard/5 min float

- 4 min Hard/6 min float

- 3 min Hard/7 min float

- 2 min FAST/8 min float

- 1 min FAST/9 min float

NOTE: As the Phase Two sessions begin to have significantly longer recoveries, move to a float & don't go easy on these.

I think you'll find each of these sessions to be surprisingly unique. They each have idiosyncratic nuances that makes them not at all the same physiological or psychological response.

I've returned to podcasting. Tomek & I now have three episodes of Fanboys! available for your listening pleasure. Expect two more series of podcasts in the coming weeks. If you want to know when they are live, subscribe to this newsletter & you'll receive an email when each podcast & new essay is posted.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, why not share it with a running friend? I would greatly appreciate it.